What does a dictator look like in

action? There is a distinctive

pattern, but it is visible not so much on the dictator’s own face as in the

expressions of the persons surrounding him or her. (Since all the dictators

that I know about and have photos of are men, I will use the male pronoun.)

The dictator is the center of rapt

attention. It is compulsory to look at him, and dangerous to show any emotional

expression other than what the dictator is displaying. Faces surrounding a

dictator mirror his expressions, but in a strained and artificial way.

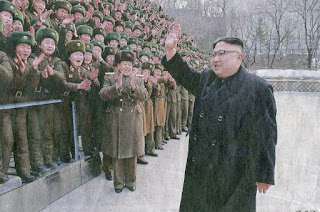

Let us examine a series of photos

of Kim Jong Un, the North Korean dictator.

Kim Jong Un smiles a lot for the

crowd, but that isn’t the striking thing. His smile is pallid and not very

warm, but the people around him are fervently smiling and applauding. They are

putting a lot of energy into it, trying to smile as hard as they can.

These are forced smiles. As

psychologist Paul Ekman has shown in detailed studies of the facial muscles

used in different kinds of emotions, smiles vary a great deal in intensity and

spontaneity. (For examples, see my blog: Mona Lisa is No Mystery forMicro-Sociology.)

Fake smiles can be easily

detected, as can the other emotions they are blended with. As we shall see,

faces around a dictator blend the required expression with give-away signs of

tension, anxiety, and fear.

It happens with all ranks. In the

following photos, Kim Jong Un’s rather perfunctory smiles are amplified by his

intently attentive generals, foot soldiers, and military women alike:

Conversely, when Kim Jong Un isn’t

smiling, nobody smiles. When he is serious, everyone looks serious. Surrounding

faces mirror his expression as best they can.

And mirror his body postures too:

Occasionally we see nervous eyes, like the man directly

behind Kim Jong Un, glancing sideways to monitor what

he is supposed to display:

Or the man who bites his lip,

peering forward to catch the dictator’s expression as he telephones an order:

The pattern is the same with the previous dictator, Kim Jong Un’s father, Kim Jong Il:

The most exaggerated

expression is the safest: Kim Jong Il’s funeral

Photos of Kim Jong Il’s funeral, after his death in December

2011, show extraordinarily demonstrative expressions of grief, among all social

groups:

Well, almost all social groups. In the following photo, the

well-dressed women of the North Korean elite show the most intense grief, as

they reach the top of the red carpet. Further back in the queue, postures are

more restrained, and the guards and attendants along the side are stolid and

unexpressive.

A notable exception is Kim Jong Un himself, who shows no

grief but looks a little worried.

The over-the-top expressions of

grief are confined to the North Koreans. Photos of foreign dignitaries at the

funeral show them somber and respectful, bowing politely but showing no strong

emotions, let alone such ostensibly heart-rending displays. These are not

normal behavior at East Asian funerals.

Compulsory Front-stage performance of loyalty

We have seen the pattern. People

around the dictator, and particular those of high rank, mirror his expressions

and re-broadcast them at even higher intensity. They put a lot of effort into

it, so that their expressions look forced and unnatural. They look

over-the-top. The dictator himself doesn’t look strained, but the people around

him do.

Their expressions are not merely

for the eyes of the dictator. He doesn’t, on the whole, appear to be giving

them too much attention. Their expressions are for each other, broadcasting the

message that they are buying into the show as strongly as possible. They are

always on-stage for each other, sending the message of loyalty to the dictator.

It is a competitive situation, to show who is most loyal of all. The competition is strongest among the

elite—those closest to the dictator—because these are the persons who pose the

greatest potential threat. Quite likely there is an atmosphere of suspicion

and denunciation, as jockeying for power and favor takes place by detecting

signs of disloyalty among his followers—or even just lack of enthusiasm. *

* A former student of mine, who

had been a teenage girl at the time of the Red Guards movement in China, told

me that the hardest thing about the omnipresent public demonstrations was

keeping up the tone of fervent enthusiasm. It was dangerous not to; it could

get you pilloried as one of the counter-revolutionaries. When I introduced this

sociology student to Goffman’s concepts of frontstage and backstage, she immediately

characterized the most onerous part of the Red Guards movement as the

compulsion to express extreme emotions that one didn’t really feel--you were always on stage.

This is why we see such extreme

expressions of grief at the dictator’s funeral—a time of most intense jockeying

for power in the succession.

The succession crisis of dictators

Even when there is a family

succession, a de facto hereditary dictatorship, there is tension. The oldest

son does not necessarily succeed (Kim Jong Un was the third son of Kim Jong

Il), since the father may weigh who is most competent at wielding power. Photos

of father and heir show a distinctive pattern:

Here we see Kim Il-sung, founder of the North Korean regime,

and his son Kim Jong Il. The son is mirroring the smile and body posture of his

father, although older man looks confident and at ease, the son more tense. We

see the same again in a photo of Kim Jong Il as dictator, with Kim Jong Un as

heir apparent:

The following photo, taken in the last year of Kim Jong Il’s

life, is revealing because of the elite audience watching the interaction

between father and son. Kim Jong

Un is leaning deferentially towards his father, showing the uncertainty and

touch of anxiety he often showed in his father’s presence. Faces of the onlookers who can see both

of them most clearly have a wary look. One man is pursing his lips to one side,

giving a distorted look to his face (Ekman notes that an asymmetrical face,

showing different expressions on different sides, is a sign of mixed or

conflicting emotions.) The

onlookers don’t quite know who they should be mirroring here:

Why close is dangerous

In a dictatorship where loyalty is always suspect and must

be constantly demonstrated, those nearest to power are the most dangerous. This

was illustrated within two years of Kim Jong Un’s formal succession. His uncle,

Jang Song-thaek, 40 years older than the young heir, acted as informal regent.

The following picture, taken during that early period, suggests guarded suspicion

between the two:

By September 2013, however, Kim Jong Un was leading the

public smiles, and his uncle was following along:

By December 2013, the uncle was arrested, tried, and

executed. Reportedly, he had plotted a coup. Or perhaps he just aroused

suspicion, by not giving off the right emotional displays. Soon after, the rest

of the uncle’s family apparently were executed too.

Since then, an older brother was killed. And the dictator is back to smiling,

surrounded by the wary, mirroring faces that characterize the dictatorship:

American tourists, too

The photo of

American tourist Otto Warmbier being brought into court for sentencing in March

2016, after two months in captivity, closely resembles the photo above of Kim

Jong Un's uncle Jang Song-thaek

being led into the same court in 2013, just before he was executed. In both cases, the arrestee shows the

same posture: hopeless downcast eyes, body slumping in extreme depression.

Undoubtedly they had been put under relentless psychological pressure to

confess, and probably physical torture.

Their offenses, at

least initially, were different: Jang Song-thaek was charged with staging a coup d'etat; Otto Warmbier with defacing or

attempting to steal a government propaganda poster from his hotel just before

he got on the plane. After Warmbier was released in a coma from which he never

recovered, a North Korean official said his punishment was for trying to

overthrow the regime.

Most likely, Otto

Warmbier, acting like an American college student on vacation, was trying to

collect a souvenir poster (the way

we used to take bullfight posters or beer coasters). But youthful pranks are not recognized in the official

culture of the North Korean dictatorship. Every expression is deadly serious in

its consequence, and every individual is under suspicion.

In such regimes,

there is no private life and no backstage fun and games. Disrespecting a symbol is taken as an

attack on the regime it symbolizes.

What can be done? That is a complicated political and military problem.

It would be an enormous step for the regime to loosen up, just to allow a space

for trivial matters.

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Civil War Two, Part 1

by Randall Collins

Giveaway ends May 24, 2018.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.